Imagine you are sitting on the banks of a river, having a picnic with a friend. Suddenly you hear yelling and splashing, someone calling for help. You leap to your feet and see that there is a person in the river, clearly in trouble.

So you and your friend dive in, and bring the person to safety. They thank you and walk away. You resume your picnic. But then you hear another voice, more sounds of splashing, more cries for help. There is another person floundering in the river. You once again jump in and help them to safety.

This happens twice more. After the fourth time, your friend turns to walk away.

‘Where are you going?’ you ask, ‘There might be more people who need our help!’

‘I’m going upstream,’ they say, ‘to find out who’s pushing them in.’

This parable isn’t new. There’s a good chance you have heard it before. I’m sharing it because a similar metaphor emerged in our research as a useful way to shift people’s thinking away from individual behaviour as the cause of and solution to crime, and help them understand how wider systems and structures impact different people and influence their likelihood to get into the justice system.

Three individuals are being swept down a river by a powerful current towards a waterfall. In the distance is a bridge labelled “opportunities” that they have missed. A man is holding out a lifebuoy to one saying “take this!” and helping him out of the water. A man on a jetty labelled “drug and alcohol support” is reaching out to another saying “grab my hand”. Two men are holding a rope across the waterfall to stop the last man from being swept over. Others have made their way out of the river with help and are walking on a path towards the opportunities bridge carrying bags labelled “well resourced”.

This parable is a good example of how the way we talk about complex social issues like criminal justice can have an impact on how people understand those issues, and therefore, on which policies and solutions they are willing to support.

So why did we think researching public narratives on crime and justice reform would be helpful?

There are many barriers to criminal justice reform. One significant barrier is what the public believe about why people commit crime and how society should respond.

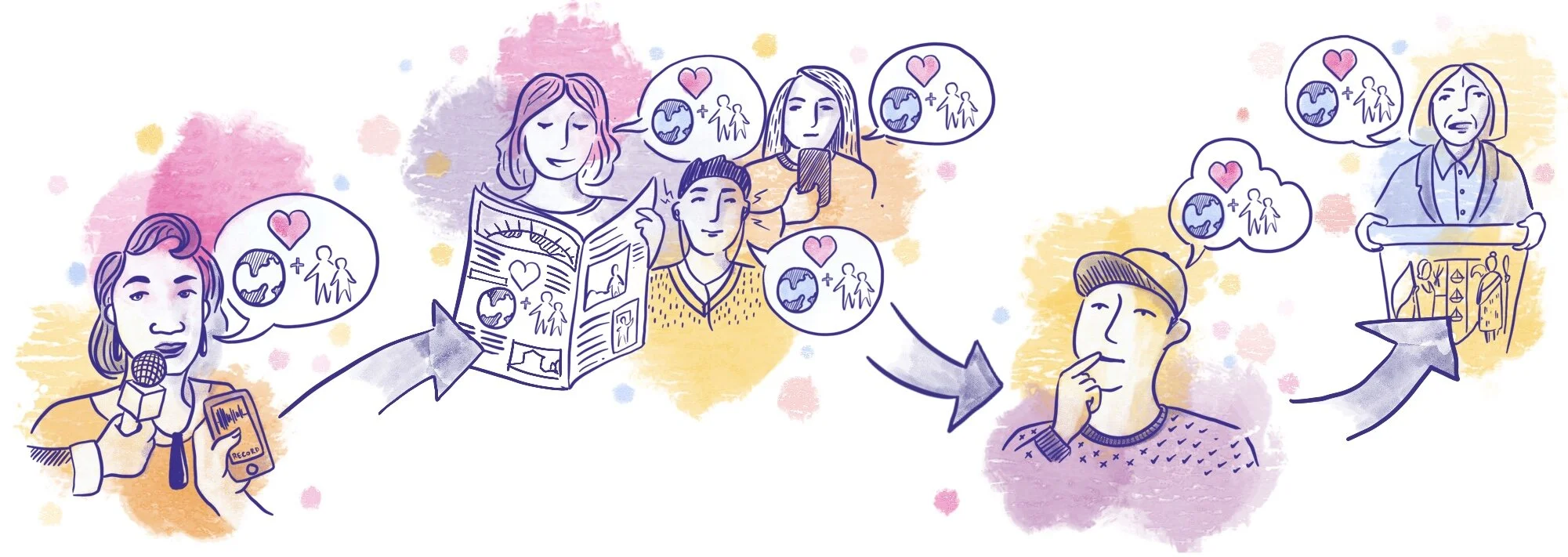

At least in part, politicians are led by public support and demand for new solutions. That public demand, and the beliefs that underlies it, is influenced by dominant cultural stories about people, crime and the criminal justice system.

When the prevailing shared cultural stories about crime and justice issues are too shallow or unproductive, it makes it hard to build support for more effective, but complex, approaches.

For example, one strong cultural narrative to emerge in this research is the belief that people commit crime after weighing up the costs and benefits of a criminal action. Where this narrative is dominant, it follows that there is also public support for solutions to crime that increase the costs to individuals (i.e. harsher punishments).

It is often assumed that if we set out the facts and evidence about crime and the criminal justice system, people will develop a deeper understanding of the issues and make decisions in the context of this new information.

Unfortunately, this strategy has been shown by research to be ineffective for building deeper understandings of complex issues. Both our in-built cognitive processes and our cultural and information environment influence how shallow or deep our thinking is about complex issues such as crime and justice.

Daniel Kahneman coined the term “thinking fast” to explain the mental shortcuts we use to reduce the work of assessing the vast amount of information we are exposed to. These mental shortcuts protect our existing beliefs and knowledge and encourage us to grasp the concrete (what we see, touch, smell and hear) and shy away from the abstract (unseen systems and structures).

At the same time, the digital age has brought new, faster and more targeted ways for us to be exposed to unproductive and shallow explanations and narratives about complex systems issues.

This all adds up to dominant beliefs and understandings.

When people have shallow beliefs about issues and our fast-thinking defaults to protect them, while shying away from complexity, it makes it hard to have productive public conversations about systemic change.

As knowledge holders and communicators on crime and justice issues, we also play our part.

We draw on the information deficit model of communication and try to ‘give them more facts’. Or we focus on compelling personal stories without drawing attention to the upstream factors hidden from view. In doing so we can inadvertently surface existing unproductive narratives, instead of navigating around them and developing new narratives.

What does this mean for building public support for criminal justice reform?

Building support for effective solutions involves dealing with often invisible public narratives and mental models. [Slide - invisible]

While dominant narratives and the mental models they feed into may be unhelpful, other narratives and mental models exist (or can be developed) that can be built upon with well researched strategies.

Rebalancing public narratives and the mental models they inform has been proven to deepen people’s understandings on complex issues.

This change happens over time when strategic communication is used across a field of practice.

Research shows that if narratives change in this way over time and, for example, crime is understood in the context of systems, structures, inequality, racism and lack of opportunity, the public’s appetite for new solutions can also change.

In the first part of this project, The Workshop and JustSpeak researched expert and public narratives about crime and justice in New Zealand. We looked to identify unhelpful and helpful public narratives about crime and justice, and to see where public narratives overlapped with expert understandings.

One example of an unhelpful, dominant narrative about the cause of crime, as mentioned earlier, is the ‘rational actor’ model - the belief that people commit crime because the rewards are greater than the risks or costs. Another is the ‘human nature’ model, the belief that some people are ‘just bad’.

At the same time, we also found more helpful, public narratives and beliefs, which overlapped with expert understanding of the causes of crime. These included:

The belief that disadvantage, economic need, social disconnection and a sense of hopelessness can contribute to crime.

The understanding that diminished capacity can contribute to crime: including drug and alcohol addictions or mental health issues.

The next phase of our research explored how experts and advocates could use carefully crafted narrative strategies to engage the more accurate and helpful ideas about crime which are present, but recessive, in the public narrative. While at the same time avoiding surfacing the unhelpful and inaccurate ideas.

We developed seven messages based on our research on expert and public narratives, and tested them using a randomised control trial. This involved allocating a representative sample of New Zealanders (3,200 people) to hear one of the seven messages or no message at all.

We tested whether each message had an effect on key attitudes about crime and willingness to act in support of justice reform. We compared this to receiving no message, where people would draw on their existing beliefs and ideas about crime and justice.

What we found - a summary

We found that over half of our representative sample of people did hold punitive views initially. But we also found that some of those people were, nonetheless, persuaded by messages about taking a more forgiving approach to justice.

We are often told to meet people where they are in our communications. If they care about safety or punishment, then we need to talk about safety and punishment to engage and motivate them. But our research shows that ‘where people are’ is rarely one fixed place.

People who hold punitive views also care about community wellbeing and can be helped to think more productively about crime and justice.

Generally, all of the messages we tested were constructed in a way that our previous research suggested would shift people in some progressive way. And we did find that these messages could potentially help move people in more progressive directions on a range of issues including:

Forgiveness (moved people in the direction of needing more forgiveness in our justice system)

Hard labour (moved people away from thinking that hard labour is a good policy)

Systemic racism (moved people towards understanding that more Māori in prison means there is something wrong with the system).

These are our recommendations based on the findings.

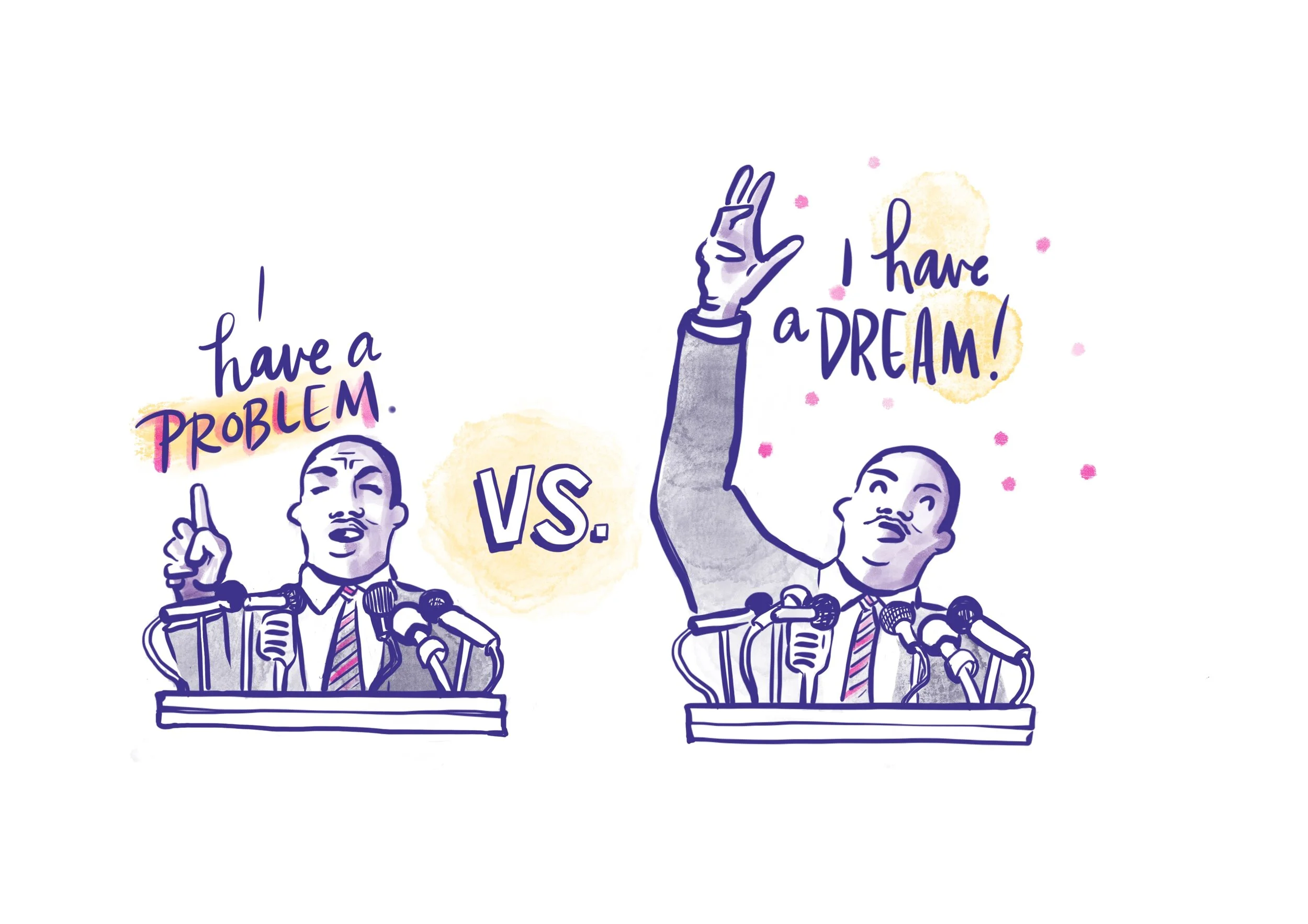

1. Start with a vision about preventing crime and restoring community wellbeing.

People take a number of cognitive shortcuts that make it difficult for them to conceptualise systems and structural change and think change is possible. Describe the better future that we want for people and communities in concrete terms to help orient people to deeper ways of thinking. Starting with a positive vision is an effective strategy.

Use collective values like pragmatism, benevolence and solving shared problems.

A person is rolling their sleeves up getting ready to fix something while reading a “how to” user manual. There is a spanner and a bolt on the table.

A growing body of research shows we need to engage all people with our shared, helpful values. Pragmatic problem solving and benevolence were the values that moved people’s attitudes in this research.

Use a small set of facts about racial inequity to help explain systemic racism.

This is a comic strip with six panels. The comic is titled with text that reads, “If we address higher rates of apprehension and imprisonment for Māori, we can improve all our lives”. Panel 1 shows a young Māori man imagining himself holding a taiaha / traditional wooden weapon, speaking in a wharenui / meeting house. He is thinking “NZ could have a justice system that improves all our lives and especially improves the lives of young Māori”. Panel 2 shows a pair of hands holding prison cell bars. There is a police car outside. Text reads, “But currently our justice system is focused on using police and locking people up rather than solving the causes of crime , like a lack of resources and services in many communities”. Panel 3 shows a woman and two young children visiting the young man in prison with text that reads, “This hurts all of us. It especially hurts Māori”. Panel 4 is split with the bottom left half showing two young Pākehā/white men sitting smoking cannabis. The top right half shows a young Māori man being apprehended by police with text that reads, “The police are more likely to pick up young Māori people than young European people for the same minor crimes, like vandalism or smoking a joint”. Panel 5 is split with the top left half showing a young Māori man and his lawyer before a judge saying, “Guilty” in a courtroom. The bottom right half shows a young Pākehā man and his lawyer before a judge saying, “Not guilty” in a courtroom. The bottom right half shows a young Pākehā man and his lawyer before a judge in a courtroom receiving a verdict. Text reads, “Māori are three times more likely to be arrested and convicted for cannabis-related offences than non-Māori with the same history of past offending”. Panel 6 shows two men in shirts and ties sitting in a wharenui / meeting house talking together, with text that reads, “To solve this problem the Government needs to work with Māori to make our justice system work for everyone”.

When we just use facts about the outcomes of systemic racism (e.g. data about the number of Māori in prison) we encounter two problems.

Firstly, a fact about an outcome doesn’t give an explanation about how that outcome was caused. People will fill in that gap with dominant mental models and narratives about what caused the problem. In many cases, especially on a complex subject like systemic racism, those ideas will be wrong.

Secondly, if we describe a problem without explaining how it was caused, it is hard for people to see how the problem could be solved. So we need to string together a set of facts that add up to an explanation about what caused the problem.

Make it clear that people in politics can do things to prevent crime.

People find it hard to imagine how issues like crime can be solved. To counter this, we need to draw people’s attention to the humans who can solve the problems we describe. This helps people believe that change is possible and see how a solution like reforming the justice system could work.

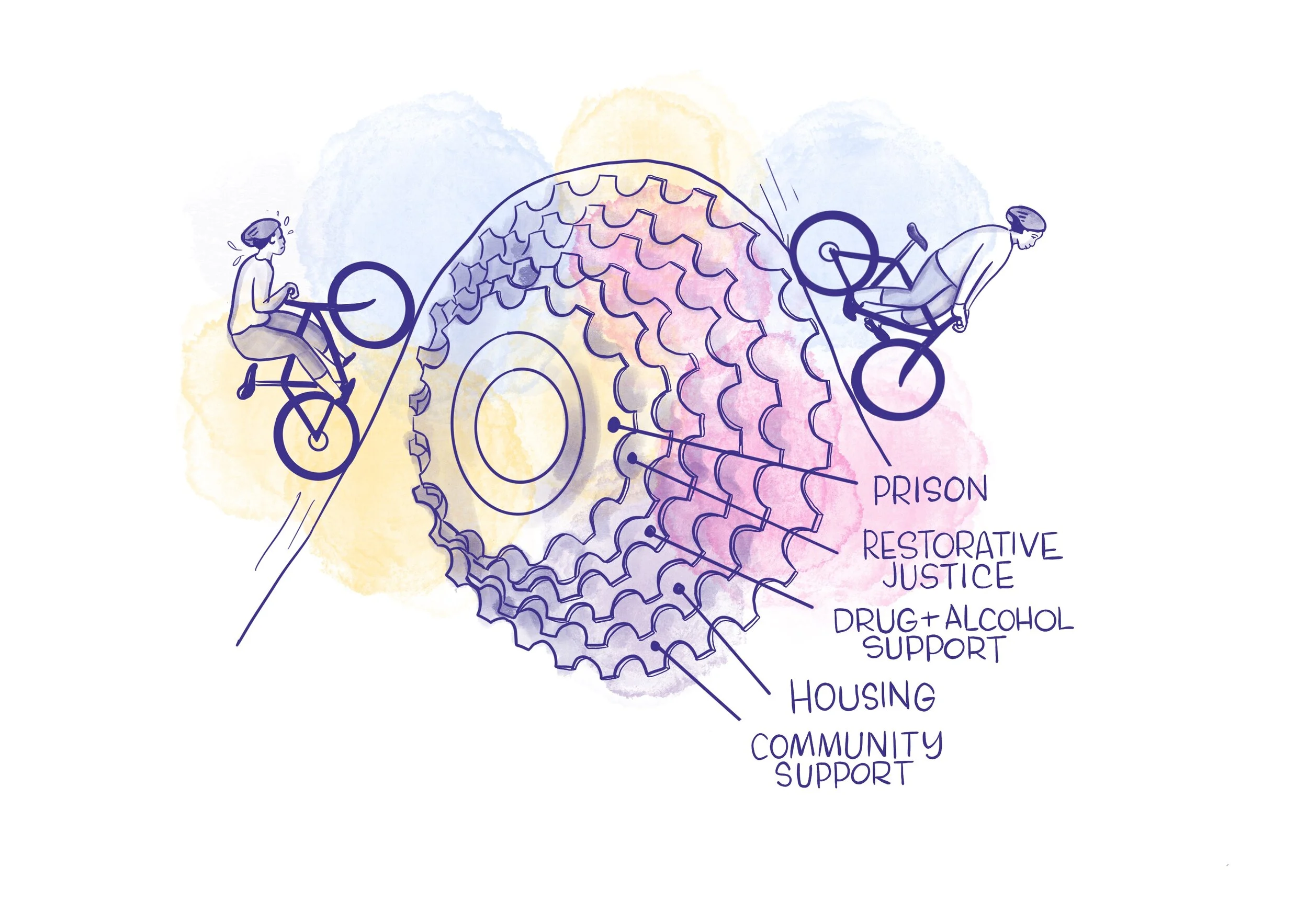

Use tested metaphors to help explain structural causes and responses to crime.

The most effective messages we tested contained metaphors that compared the justice system to a ‘maze’ and ‘gears’. We recommend using these metaphors.

A hill is represented by a bicycle gear cluster. The most difficult gear is labelled “prison”. One person is struggling up the hill on their bike using this gear. Another person is happily speeding down the hill on their bike as they have been able to use the easier gears labelled “restorative justice, drug and alcohol support, housing and community support”.

These results are presented in detail in the message guide, which you can download here.

Research shows that shifting public narratives requires us to start with understanding how people currently explain the problem. Then we develop an evidence-informed and tested strategy to help people shift to more accurate and helpful beliefs and understandings. That’s what we’ve done so far. But none of that will make any difference unless people in the field of practice use this strategy. So that’s what comes next.

Our own research tells us that simply presenting people with new information is not enough to shift how people think about issues or how they practice, so the next phase of this project will involve us developing and testing - hopefully with the help of some of you - an interactive workshop at which people who communicate about crime and justice can explore with us how these messages and strategies might apply or be useful in their work.

Before I finish, a quick note about the COVID memo that we wrote to go with this message guide.

Since we carried out the research for this guide a global pandemic has changed many things, including how people view justice reform and the policy context in which many of you are working to achieve justice reform. So we took the opportunity in this memo to reflect on the communication strategies used as part of the COVID-19 response. What were the narrative strategies that helped to build public support for significant changes to how we thought about each other and our actions? How could similar strategies be employed to build support for justice reform? What did we learn about what not to do?